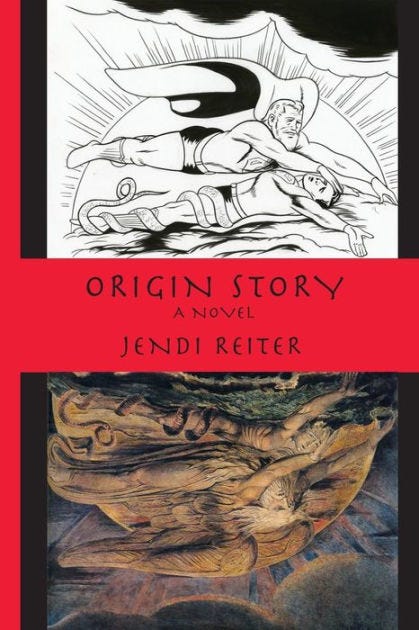

A Review of Jendi Reiter’s Origin Story (Saddle Road Press, 2024)

Jendi Reiter’s Origin Story (Saddle Road Press, 2024) begins with shock and awe: Peter Edelman strangled in his bed, shuddering post-orgasm, vibrator wrenched in his ass.

Not to worry, though. It’s just Peter and his boyfriend engaged in some vigorous bondage and masochism while the apple cranberry pie finishes in the oven.

Peter and Julian do a lot of that in this book. Sex, that is. The pie is only for this opening scene. It’s to bring to dinner with Peter’s family, and to infuse a scene of queer kink with some homestyle Betty Crocker bliss. I’m not a connoisseur of gay erotica, but I’d like to know more about that pie. Peter gives it an extra ten minutes in the oven to crisp, but it dries out. My guess is seven would have hit the sweet spot, but pie was the last thing on Peter's mind three minutes ago.

Now the oven timer's going off and there's a sense of urgency. If Peter doesn't get the pie out the smoke alarm will be calling next, but Julian senses something else.

"Did I hurt you?" he asks, as he unties Peter's wrists.

Peter, a twenty-something social worker in New York City in the late 1990s, has been having anxiety episodes. He self-medicates with street weed—the only kind available in the nineties—and sometimes pays a guy in a dungeon to put him through a rape scenario.

"Not enough," Peter teases.

Peter is happy and spent, but sex can be tricky for him. His 'not enough' is saying more than he knows. He fucks like he's digging out a splinter. As it goes with sexual trauma, the body remembers what the brain forgets, and the repressed memories that underlie Peter's need to be tortured are hidden, literally, up his ass.

He's also into comic books.

He’s creating his own series, called The Poison Cure, in which his hero, a greenish character named Pharmakon, rapes child abusers to death. This is an impulse I can relate to (though I’d rather poison the cake). Excerpts from Peter's series appear throughout the book, and though every episode is charged with sexual passion and malice, they ultimately leave him dissatisfied because after the justice-without-due-process fantasies end, he still lives in a world full of child molesters not facing consequences, and his anxiety and self-destructive behavior worsen.

I don’t wish to give the wrong impression; Origin Story is a good read. The main character’s interests are different than mine, but the book is fun; the scenes are energetic, the dialogue fresh and often humorous despite the dark subject matter. We get to know Peter and Julian on an intimate level through Reiter’s extensive tour of their lives. Readers who do not gravitate toward dick scenes or comic books may appreciate that those elements are neither arbitrary nor gratuitous. Peter's intimacy with Julian leads him to the trauma at the root of his anxiety, and his exploration of his caped hero’s motives helps reveal who his own culprit is.

In fact, Origin Story offers a rare and critical picture of child abuse by a perpetrator that too many would be unable or unwilling to accept.

The type of scenario we often see is here too—middle-aged man, confused kid, comic bookstore stockroom—but Peter doesn't regard this man as an abuser. Grownups fucking teenagers was normalized in the nineties. In movies and popular media, too, which is why the twenty-first century began with a #MeToo movement. This man—this comic bookstore owner—as Peter's first-person narrative explains, is the man who taught Peter how to be gay.

The person who Peter acknowledges as his abuser will surprise many readers. It is a person who can hide their guilt beneath webs of societal dissonance. Like pastors, cops, teachers, doctors, other identities that enjoy the unearned privileges of social trust, they operate under the delusion that such and such a person could never do such and such a thing. Unless they confess or are exposed, their victims are forced to live under this delusion as well, which is a perpetuation of the abuse, and anyone helping to maintain the delusion participates in that abuse. As a societal delusion, that means a hell of a lot of people are in on it, and that, I can tell you, leaves a victim feeling pretty isolated.

Fortunately, for people like me and Peter, there are people like Tai.

Tai is the gender fluid teenager in the orphanage where Peter works. I initially thought Origin Story would be about her—four of the sixteen lines of back cover copy are about her—but she appears in only a handful of scenes throughout the book. So Tai is a device. Like Peter’s comic book script, she exists to help Peter understand himself.

They call her “Tyler” or “Ty”. Peter describes her as a “ripped black Dominican dude in scarlet lipstick.” Her intake paperwork says she “believes he has an alternate female personality which he calls ‘Tai’ and periodically demands to be addressed by this name and female pronouns.”

The orphanage director says “Tyler’s” gender confusion is dissociation from trauma and directs her staff to discourage her feminine expression, while they casually traipse across ethical boundaries with her. When she displays a talent for drawing, they confiscate her sketchbook. After perusing her drawings, Peter is struck with a sudden urge to visit his BDSM dungeon. He enlists her to create the artwork for his erotic comic books, and gets her a job at his middle-aged former employer’s comic bookstore, accepting the store owner’s justification that it'll be ok because Peter was only thirteen when he was being violated in the stockroom by the boss, whereas Tai is fifteen.

I’d say it's an authentic rendering of therapeutic environments in the nineties, when unethical behavior was rampant and qualified treatment was slight.

Tai is called difficult when she won’t respond to her masculine name. Tai is a “rebellious clown,” says Peter, but the only thing she is shown rebelling against is the orphanage’s rejection of her identity.

Tai says, “My clothes are wrong. My body is wrong. I look down and expect to see something that isn’t there.”

Tai pleads with her social worker to believe in her, but we must remember she only exists as fodder for Peter’s contemplations about the different aspects of his inner self: Staring at himself in a mirror wearing his goofy Banana Republic octopus shirt, he wonders, Can two minds get along in the same brain?

As a device, Tai has no arc. She doesn’t grow or change in the story. She is firm in her identity in the beginning and she is firm in the end, and I wonder where all that confidence comes from. How is she so self-aware yet so young? Does she keep her confidence in the years ahead, or will she end up back in the closet like I did? Tai is constantly asked to accept that something is wrong with her, when she knows deep down there is nothing wrong with her, and if people would stop treating her like a boy just because she looks like one, these “mental health diseases” would all go away.

“Do you believe in Tai?”

She says to the other girls, I’m one of you, can I be your friend?

And they say, eww, no, you’re a boy.

She says to the fat girls, the pimply girls, the girls whose noses are too big or whose eyes are too close together, You think you have it bad? Look at me. And they say, You’re a boy, you’re supposed to look like that, and she says, no, I’m a girl, and I look like this.

Eww.

They say do you have a vagina or a penis? She says penis.

Eww.

Yeah, dick repulses her, too, but hers gets her classed with the gays (the men who want to be with men), so this girl who wants to be treated like a girl and allowed to live in the girl’s world gets placed in a double-testosteroned, doubly sexually-charged, double-male world because she’s too eww for the girl world.

I have a lot in common with Peter, but I see myself in Tai. I was Peter's age in the late nineties facing the same culture of resistance and internal loathing while trying to solve the mysteries of my sexual initiations. I have my own version of a comic bookstore stockroom, similar struggles with PTSD. And I have a Tai, my own little self-assured guide leading me to self-acceptance. But my Tai is not a character in a book or the hidden inner self of another person; she is the previously hidden inner self of this person. My Tai is called Heather.

I was born “Aaron”, but wished it were “Erin”. I called myself “Dusty” from age seven to forty-nine. “Annabel” is what the voice in my head calls herself, and now that she’s out, she likes to go by “Heather”. I’m a clusterfuck. And, yes, Ms. Orphanage Director, it is dissociative and does result from trauma, but I don’t call it a disorder. I call it a highly organized, miraculous work of fucking art.

Growing up, I learned to speak English. I identified as a boy. I was taught to love Jesus and I was abused a lot. These were all formative experiences. None of them is any more or less a part of me than the others. Aaron, Erin, Dusty, Annabel and Heather are products of all that shit, and I am all those people.

Heather doesn’t “pass” easily for a woman when I wear the clothes she likes to wear. I don’t cinch, pack, pad or tuck things in places. It’s just me under this dress. They told us in the Navy that to get big, manly arms you have to work your triceps, so I did that, and now my arms look pretty manly in a sleeveless dress.

Peter would probably call me a rebellious clown, too. I make a damn fine carrot cake, but I'd serve Peter a big slice of sweet potato pie because, as Popeye says, I yam what I yam.

The thing about a Tai or a Heather is we don’t tolerate a lot of being pushed around by the world. We were born inside a single person’s creative mind, and while the exterior took a beating, we were allowed to grow according to our own capricious will. They call us difficult when we come out because we have to be tenacious. We’re entering a world previously so ill-fitting that it forced us into years of hiding in suicidal isolation.

Peter is trying to destroy the dark thing that festers inside him, but Tai says no, Peter, you have to bring that thing into the light. What Peter doesn’t understand is that the dark thing he’s trying to kill is him. To be transformed by such a device as Tai, he must learn, as I did, to treat the dark thing like it’s beautiful, because it is.

HEATHER JONES is a writer and trans woman based in Maine. She holds a master’s degree in Behavior Analysis from the University of North Texas, and recently earned her MFA at the University of Southern Maine where she also served as Online Editor and Art Director for The Stonecoast Review. She is a regular contributor to the Gender Defiant newsletter on Substack, and her letters to the editor have appeared in Playboy Magazine and The New York Times. As a sailor in the US Navy, Heather has circumnavigated the earth. As a survivor of a restrictive religious upbringing, her work is often irreverent, iconoclastic and reflective of her lifelong quest for answers.